English Strange

The Britannia Coconut Dancers of Bacup in Lancashire continue their unique tradition with its origins lost in centuries past. Derek Schofield looks behind a dance that survives with pride.

Bacup town centre at 8am on a Saturday morning is probably much like any other. Shops are starting to open, delivery vans zip around the largely deserted streets and the occasional pedestrian is off to work. Even on the Saturday of Easter weekend. I’ve parked my car and now I’m searching for a quick cuppa before catching the Rochdale bus through the area of town known as Britannia to alight on the town boundary at the Travellers’ Rest. It used to be a pub, but it’s closed now, converted to offices. Here, there’s more activity. Groups of people are waiting, expectantly, while strangely-dressed men and silver band musicians greet each other in friendship.

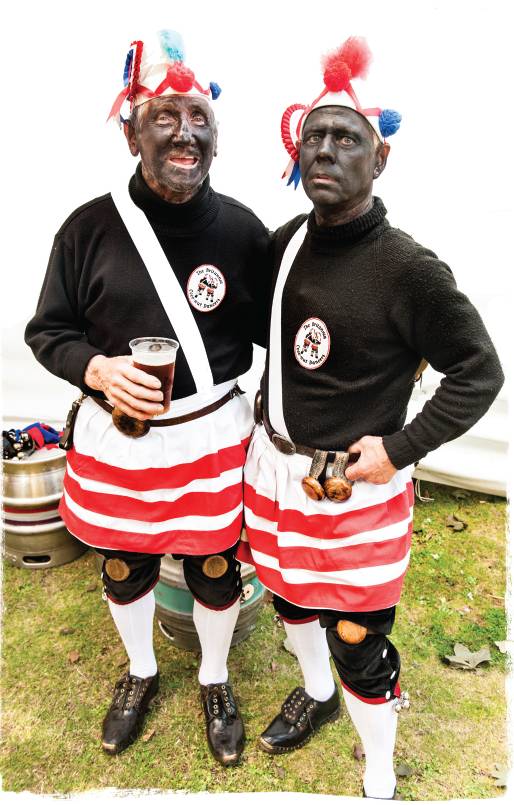

Each strangely-dressed man wears black breeches, long white socks and black clogs. Over a thick black jumper is a white strap which helps to hold up a white skirt – the men prefer the word ‘kilt’ – which has three horizontal red stripes. On his head is what looks like a short, squashed chef’s hat decorated with a rosette, zig-zag ribbon round the base and a feather. On his knees, waist and in each hand, he has a disc of wood. Oh, and his face is blackened. I said it was strange.

On the dot of 9am, the dancers (for that’s what they are) line up in a square or quadrille formation, holding semi-circular garlands decorated with red, white and blue crepe paper. The band strikes up, and they’re off on a dance which lasts no more than a couple of minutes. Next, the dancers line up with their backs to the ex-Travellers’ Rest, and a different dance involves the men pointing at each other, cupping their ears with their hands, and striking their own and their partners’ … erm … nuts (don’t worry, that’s what the discs of wood are called).

The dance over, the men split into two groups of four and stand on each side of the road; with the band walking in a line down the street, the dancers follow – first one line, then the other, stopping alternately to perform a few dance figures. In this formation, the dancers process down the road until the next stopping point (site of another, long-closed pub). And so it continues in similar fashion for the next ten or more hours – stopping at pubs (open and closed), a residential care home, the fire station, into the town centre and out the other side, through the settlements of Stacksteads (base of the silver band musicians), Water-foot and Tunstead until they reach the opposite town boundary on the Rawtenstall road, finishing at – yes, you guessed it – another long-closed pub, or more accurately, the petrol station opposite.

I’ve been making this visit, off and on – but mainly on – since the 1970s, and it never ceases to fascinate.

In all, there are five different garland dances, each one lasting no more than a few minutes. In contrast to the exoticism of the costume, the dances and the tunes are known plainly as number one, number two, and so on. The nut dance can be performed in its full version, or cut down to just half the number of figures, or in two lines facing each other, or in square formation (which they call Figures Of The Nuts), or in the processional formation down the road. Each version has a core of common movements and figures, with variations. On Easter Saturday and other occasions, the music comes from members of Stacksteads Silver Band, established in 1872 and currently enjoying success in band competitions in the region. Links between the dancers and the band are even closer these days as Coconutters’ secretary Joe Healey and his twin brother Tom are also band members. At other times, the dancers are accompanied by several English concertina players.

Recently appointed leader of the Coconutters, Ronnie Searle has been a dancer for 31 years, which though impressive, is nothing compared to his predecessor, Dick Shufflebottom, who retired as leader at the age of 80 after 58 years as a dancer – and he’s still dancing. He’s an inspiration to the recent influx of younger dancers – Gavin McNulty, the son of established dancer Martin, and friends Luke Cooper and Ellis Stericker who are just into their twenties. Such very young dancers are unusual. Gavin tells me that the team has traditionally looked for committed family men and, like his predecessors, he had to make a written application, explaining something about himself and why he wanted to join.

The town of Bacup (the first part of the name rhymes with bake, not back) lies at the eastern end of the Rossendale valley in Lancashire, near where the river Irwell starts its journey towards Salford. The industrial revolution brought cotton mills, quarrying and coal mining to the town – all gone now, and although the shoe and slipper firms no longer manufacture, they do operate distribution and retail outlets. English Heritage reckons it’s the best preserved cotton town in Lancashire.

On the streets of Bacup…

…and starring at Sidmouth Folk Week

Last summer, the Coconut Dancers returned – after a gap of ten years – to Sidmouth Folk Week. As they finished their performance at the Late Night Extra, a friend stood next to me turned and, with a bewildered expression, asked, “Where does this come from?” Ah, if only we knew! The Coconut Dancers don’t fall neatly into the categories of folk dance that Cecil Sharp and his later supporters devised in the early 20th Century. They don’t resemble the morris dancers from the north-west of England, although like the morris dancers, there is the processional nature of the street dance, and there’s the seasonal performance.

There’s a newspaper report of them in Sharp’s press cuttings book, so he did know of their existence. In 1927, Anne Gilchrist included the tune of a Coco-nut Dance, dating from Rochdale in the 1850s, in an article on Lancashire morris dances – the source of Spiers and Boden’s arrangement of the tune for the duo and for Bellow-head, although this tune is unlike the current Bacup tunes. In 1929, Maud Karpeles visited Bacup and noted the garland dances, although the dancers were reluctant to let her note the nut dance. They obviously realised that they had something unique, and did not want anyone to copy it.

They were soon feted by the English Folk Dance Society, and its successor the English Folk Dance and Song Society, travelling to London to dance at their Royal Albert Hall festivals. The Society explained the dance within English ceremonial dance traditions defined by Sharp, and Douglas Kennedy, Sharp’s successor as director, was happy to authenticate it as a “true morris coconut dance”. But that doesn’t answer my friend’s question.

We do know that in 1907, the Tunstead Mill Coconutters celebrated their golden jubilee, Tunstead being an area of Stacksteads. A detailed press report gives names and details of costume, route on Easter Saturday and music – all similar to the current-day Britannia team. Theresa Buckland researched all the occurrences of coconut dancing in the area for her doctoral thesis, tracked down descendants of former dancers and wrote about the Tunstead Mill group in the 1986 Folk Music Journal. The Tunstead Mill group seems to have disbanded by the outbreak of the First World War, but they taught the dances to the Britannia team in the early 1920s, although the current dancers reckon they were founded soon after 1900.

But that still doesn’t answer the question! Of course, there is no simple, clear-cut answer. There are, however, some clues. In his researches into 19th Century occurrences of morris dancing on the stage for his 1997 Folk Music Journal article, the late Roy Judge refers to an 1824 production of a play that features “A New Cocoa Nut Dance”, and such a dance then appears in other plays into the 1830s, with a description that coconuts were held in the dancers’ hands and struck together. By at least 1836, the dance becomes detached from plays, with the Chiarini Family performing their “Cocoa Nut Ballet” at Ryan’s Circus in Bristol. Other families got in on the act, and there are newspaper adverts for the “Cocoa Nut Dance” throughout the 1830s in Bradford, Birmingham and Gloucester, for example. None of this proves that such a stage performance was the origin of coconut dancing in Bacup, or, vice-versa, that the Lancashire tradition inspired the stage show. Intriguingly, there’s also a reference to mid-19th Century morris dancers in North Leigh, Oxfordshire, holding coconut shells in their hands for one dance, and there were coconut dancers in St Mary Cray, Kent, in 1893.

In Bacup, the Coconutters have a more localised explanation – they reckon the dance came from Cornish tin miners who settled in neighbouring Whitworth and who taught it to local quarrymen. And that when the dancers hold their nut-filled hands to their ears, they are mimicking miners listening for rock falls in the coal mines. Black-faced coalminers, and a desire for disguise, also explain the blacked-up faces. Knowing the Coconutters, and talking to them as part of the Sidmouth A Chance To Meet event, I sensed that they were less interested in hypothesising about possible origins, and more interested in the continuity of the dance tradition into modern-day Bacup.

Joe Healey says of the dance, “It’s been revered in our village and it reflects our hard industrial past. Our forebears and our present generation respect that; we are caretakers of that tradition, each and every one of us who give our time freely to it. And each time we go out and dance, and especially on Easter Saturday, we are paying homage to the past men who danced this tradition and upheld it, and we’re very proud to do so.”

Dick Shufflebottom & Ronnie Searle

Pride is a word that easily springs to mind when considering both the dancers’ attitude to the tradition, and the local response to the Coconutters. The local Rosso Bus company has just emblazoned one of its buses with the name and pictures of the Coconutters. And in the town centre, there’s the Nutters’ Garden – part of the local heritage trail, with an information board and images of the dancers. On Easter Saturday, local organisations and businesses take full opportunity of the influx of visitors and the festive atmosphere, with special markets, stalls in the town centre and children’s events, while the volunteer-staffed Royal Court Theatre and natural history museum are open to visitors.

That pride came to the fore a couple of years ago when the whole Easter Saturday tradition was threatened by a combination of police and county council restrictions. With recent austerity measures, the police insisted either that they were paid to manage the traffic, or that stewards be professionally (and expensively) trained, or that traffic control be outsourced to a specialist company. Without one of these options, the county council threatened to refuse the dancers a licence to perform. It’s a problem that other street events up and down the country are also facing.

The matter has been resolved – for the time being – thanks to the county councillors from Bacup using their discretionary funds to pay for a traffic management company. But before this happened, there were meetings, support from local businesses, publicans and local Bacupians, and even a national petition. As dancer Neville Earn-shaw says, “The county council don’t appreciate what a following the Nutters have. They take us on, and they lose!” www.coconutters.co.uk